This is not the first Suspension Deep Dive I’ve written that featured a McLaren. The last one happened just over 10 years ago, if you can believe it, after a colleague and I had the chance to photograph an early naked rolling chassis of the MP4-12C before it went on sale. But this McLaren GT came to me as a fully operational machine, which allowed me to scrutinize it in my own driveway.

That meant using my own tools, of course, which was frankly nerve-wracking when it came time to lift it. But it wasn’t as bad as I’d feared, as the jack points (more like zones) were clearly marked with stickers that depicted a floor jack icon that looked encouragingly like my own aluminum race jack. What’s more, I’d recently bought soft rubber jack and jackstand pads meant for safely supporting vehicles such as this.

Thing is, the GT sat so low that I couldn’t slide my floor jack underneath without additional measures. In front, this simply meant raising the car’s nose lift, which we’ll see later. But the rear has no such system. To gain the needed clearance I had to drive this quarter-million-dollar GT up onto a 2×6 laid flat on a square of plywood as if I were leveling a motorhome to make the fridge work properly.

Yes, really.

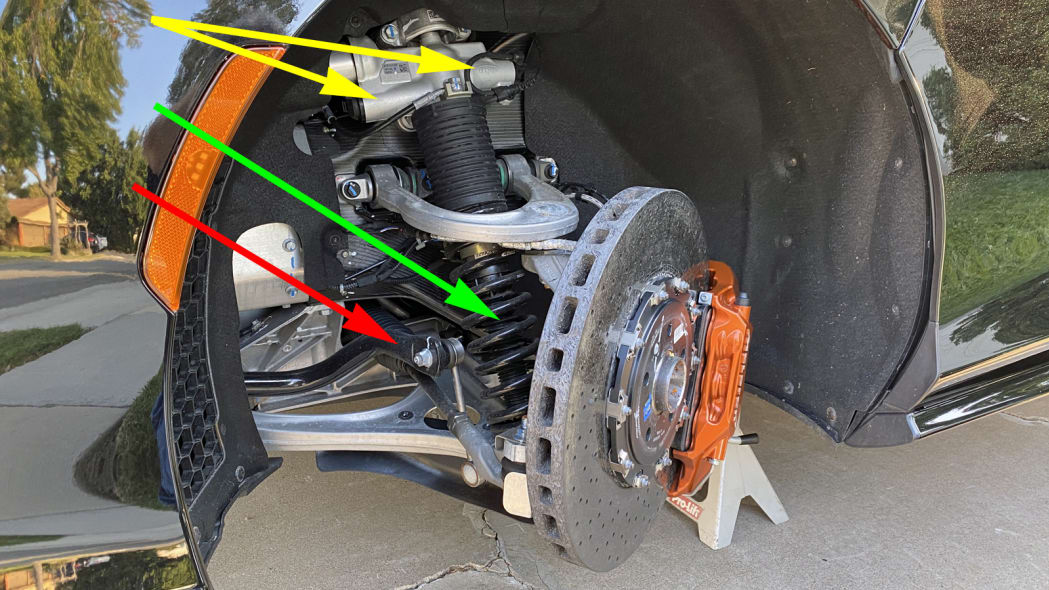

Even with the front wheel safely removed, the GT’s huge carbon-ceramic brake rotor blocks most of the view and makes it hard to see much of anything else. The main exception is the top end of what looks like a somewhat familiar damper assembly.

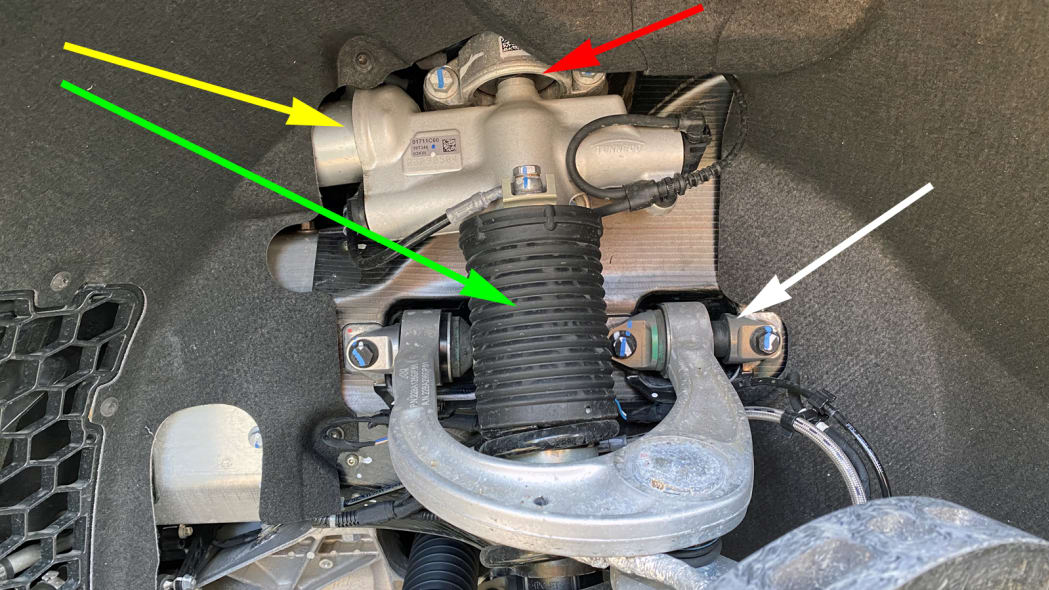

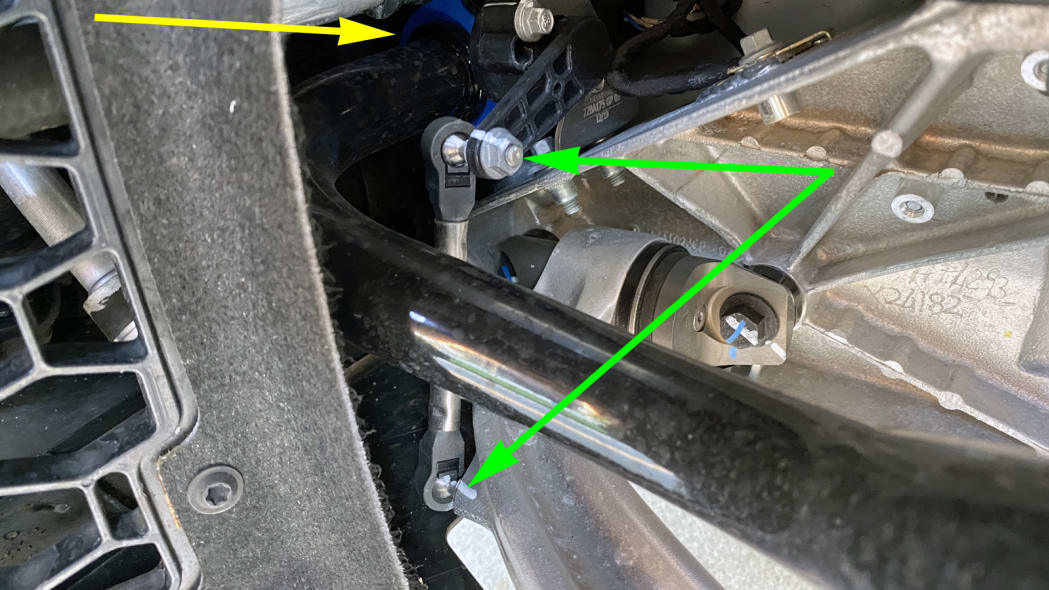

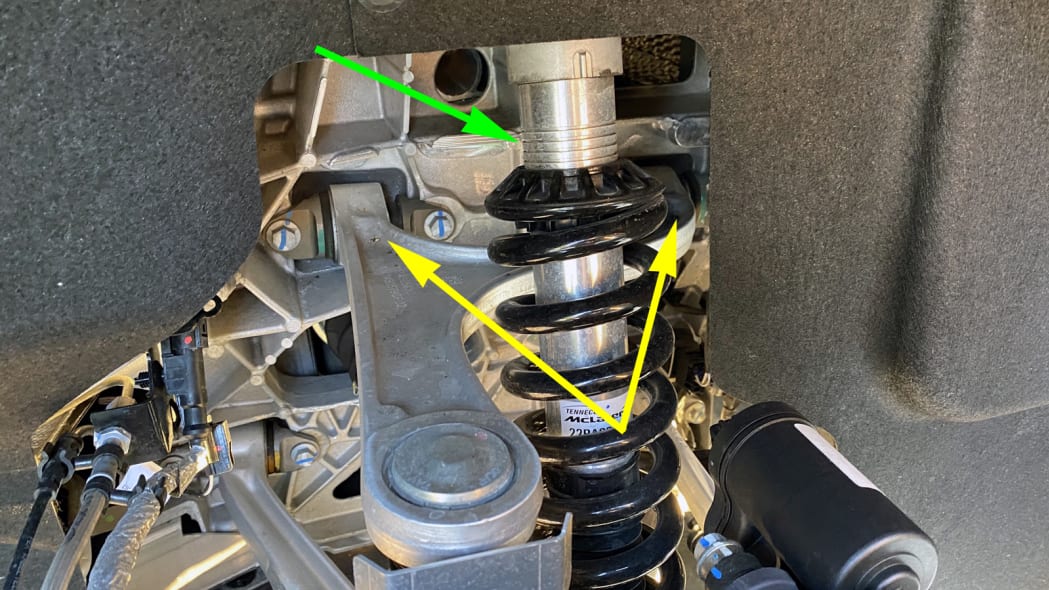

Like the MP4-12C and 720S, the McLaren GT’s shocks are inverted to minimize unsprung mass. The damper’s narrow shaft (red arrow, and hidden by a protective telescopic boot) makes up the moving end at the bottom, while the more massive business end and its horizontally arrayed and electronically controlled damper valves (yellow) are fixed to the chassis at the top. The higher of the two lumps is the compression valve, the lower one is the rebound valve.

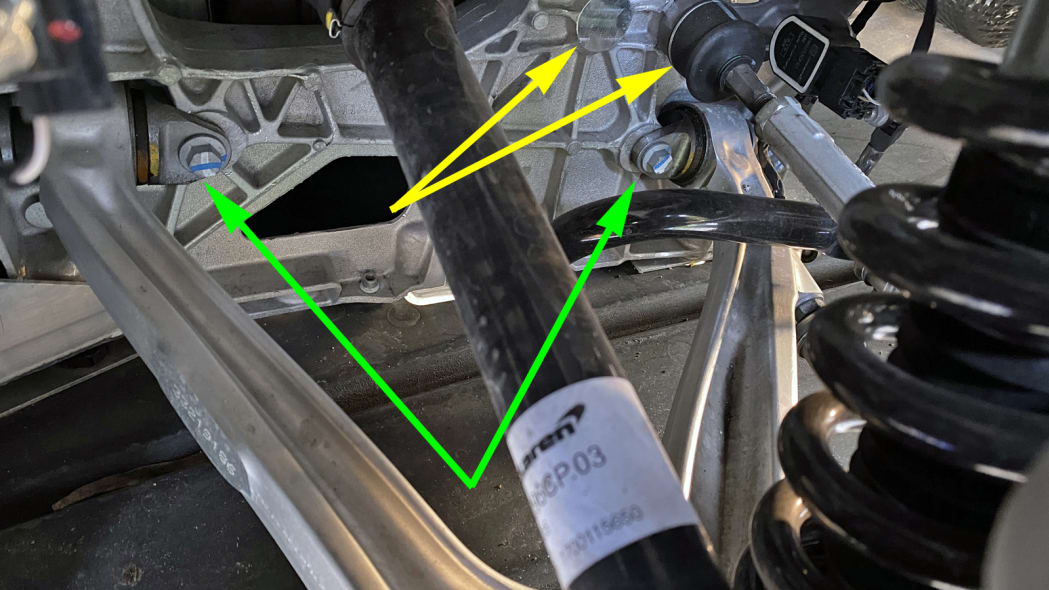

The McLaren GT parts ways with the MP4-12C and 720S at this point in a big way. Those Super Series cars have a kinetic hydraulic roll stabilization system, in which transverse piping links the compression valve on this side to the rebound valve on the opposite side, and vice-versa. But here we see a traditional stabilizer bar (red) of the same sort as the 570GT and 570S, albeit with a different specification that befits the GT’s role as, well, a GT.

But the GT isn’t entirely like the 570 series, either, because here the electronic dampers use the 720S’s advanced sensor suite and its Proactive Damping Control software that analyzes driver inputs and the incoming road surface using something McLaren calls Optimal Control Theory in order to project forward from the current condition and predict what the car will need in the very near future. The idea is to deliver the damping force the car needs when it needs it, and they’ve got the lag down to just two milliseconds.

The bellows above the spring (green) protects the hydraulic front lift system that kept the GT from making horrible scraping noises when I pulled it into my driveway. An accumulator (yellow) connected via a hydraulic hose makes this work. This feature is technically an option, but McLaren says that 90 to 95% of GTs will have it.

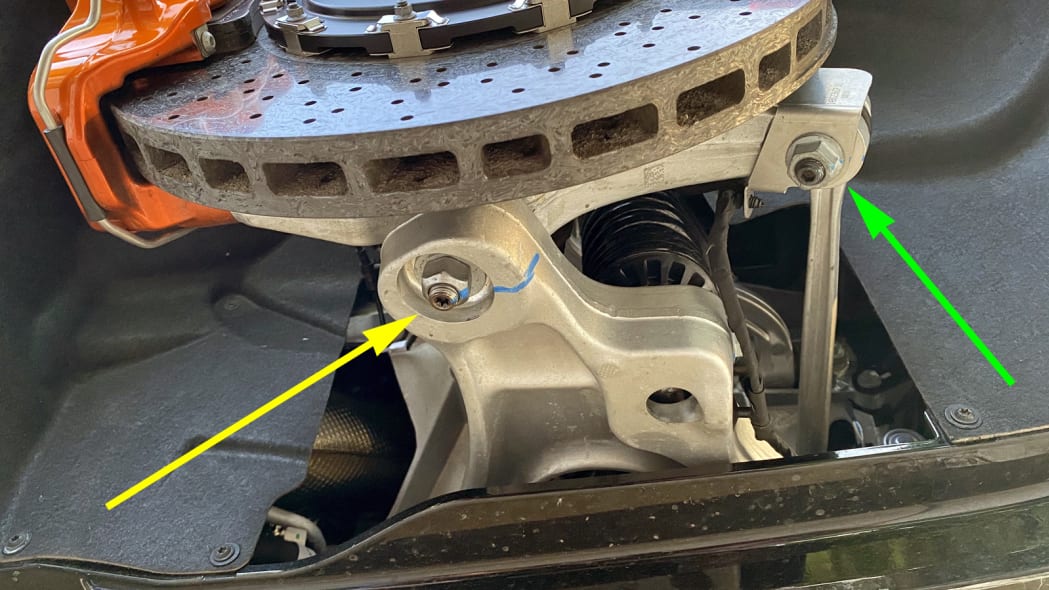

The damper’s upper attachment is bolted to a circular halo (red) that is in turn bolted laterally to the carbon fiber chassis. Variations on this low-profile arrangement are found on all McLarens, and the objective is to keep the hoodline low. Lateral tie-bars (white) are used to attach the suspension arms to the chassis. We’ll be seeing a lot more of these.

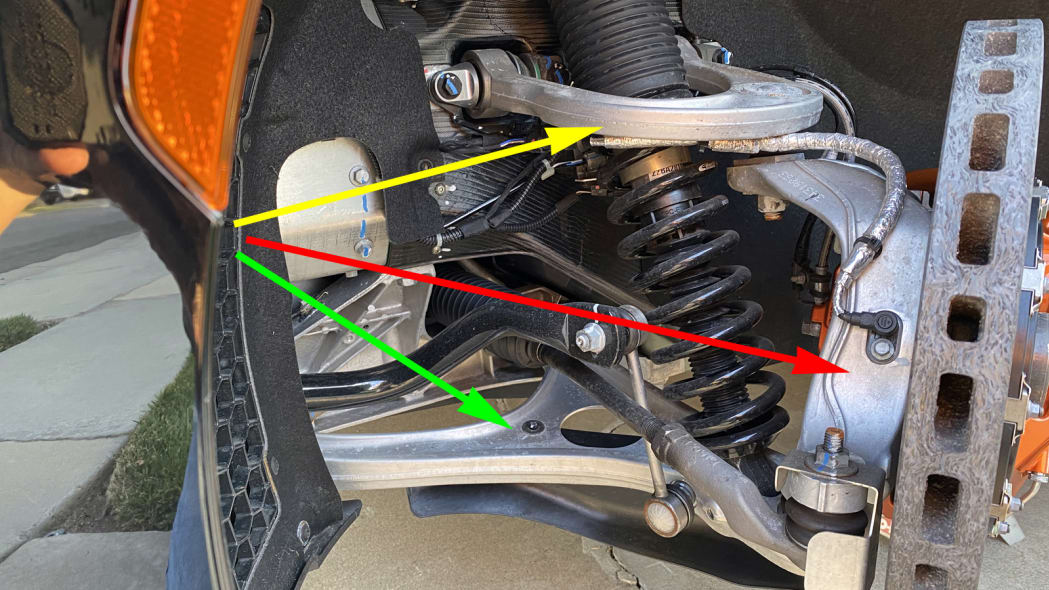

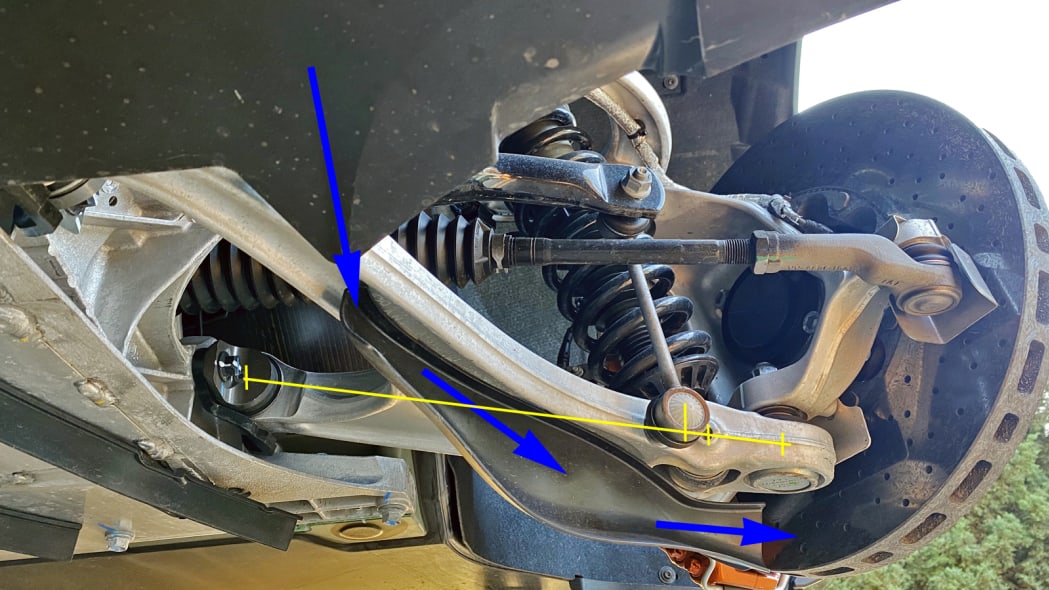

This is clearly a double wishbone suspension, and the upper wishbone (yellow), lower wishbone (green), and suspension upright aka knuckle (red) are all made of forged aluminum.

Lateral cornering forces feed mainly into the rear leg of the lower wishbone (yellow) because they line up. Meanwhile, the forward leg (green) handles longitudinal forces. In fact, the downstream face of the rear leg’s bushing (purple) doesn’t even have a cushion to help out.

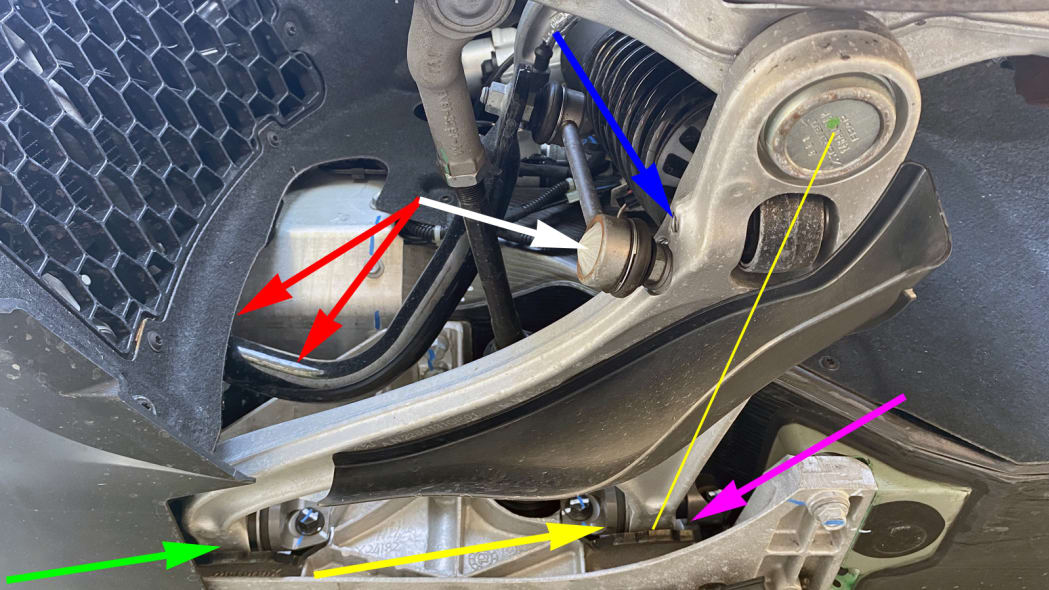

Higher up, the conventional stabilizer bar (red) bends behind the fender liner toward its pivot bushing. Out at its end, the end-link (white) is fairly obvious, but its lower arm attachment point doesn’t quite line up with the mounting bolt (blue) for the coil-over shock.

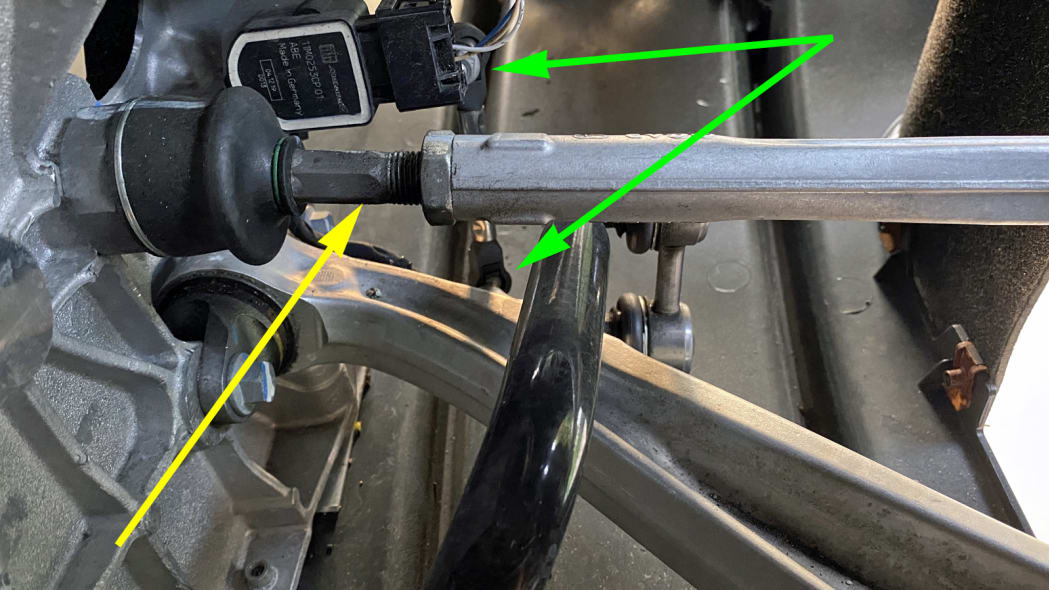

A peek behind the fender liner reveals the stabilizer bar’s pivot bushing (yellow). We can also see where the suspension position monitoring sensor (green) attaches to both the chassis and the lower wishbone.

You’ve probably worked it out for yourself that the gracefully curved black plastic add-on directs cool air (blue) toward the front brakes. As for the yellow line and tick marks, they show that the stabilizer bar’s motion ratio is on the high side of 80% compared to wheel motion, while the spring and shock sit slightly farther out at something closer to 85%. The damper’s greater lean angle offsets this delta somewhat, so the difference may work out to nil.

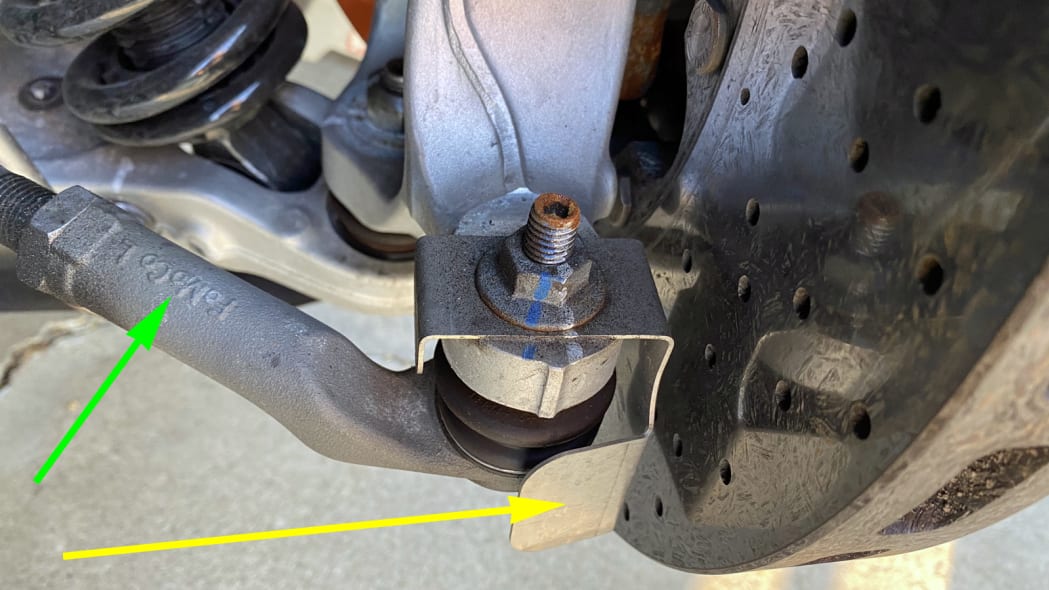

These simple heat shields (yellow) show up on the GT wherever rubber-sealed ball joints reside close to the potentially red-hot brake discs. As for the steering tie rod itself, that Ford Motor Company parts logo (green) makes me wonder which car this piece comes from.

The GT’s central carbon fiber tub (green) makes up the majority of the chassis and is the attachment host for the upper wishbone and the top mount of the coil-over shock. We’ve also seen an aluminum subframe that carries the lower wishbone and the stabilizer bar bushing. Here we can see how those two major components are bolted together (yellow) to act as one structure.

At first glance, the McLaren GT’s six-piston front calipers seem tiny after you’ve seen the humongous 10-piston monsters on a Porsche Taycan Turbo. But there’s a simple reason: the GT weighs a lot less than a Taycan. How much? Almost a ton or 1,748 pounds, to be exact.

But it goes beyond that. McLaren decided that lighter calipers were worth the tradeoff in extra flex because they really wanted to minimize total mass and unsprung mass. They were able to mitigate the potential negative effects a driver might otherwise perceive by employing a more aggressive ratio in the brake pedal linkage.

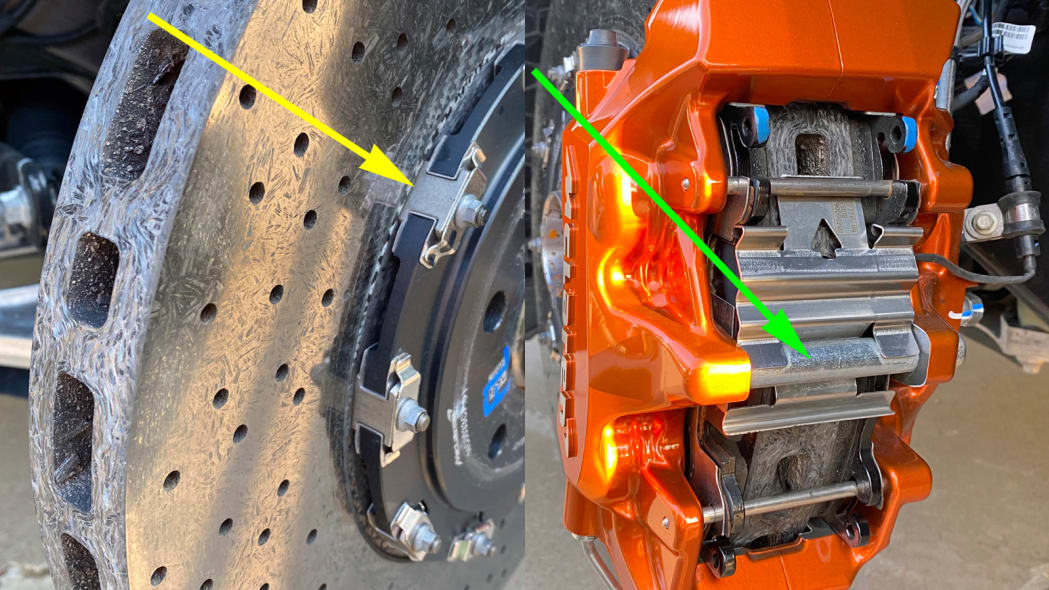

The rotors are two-piece assemblies made up of an aluminum central hub and either a standard cast iron or optional carbon-ceramic rotor. Two-piece seems like a bit of a misnomer, as there are 10 bolted joints made up of at least five pieces (yellow) that we can see. This arrangement allows for heat-related dimensional changes to occur without feeding vibration back through the system.

Meanwhile, the AP Racing caliper uses an open-window design that gains extra stiffness from a bridge bolt (green) that is removable when it’s time to change brake pads.

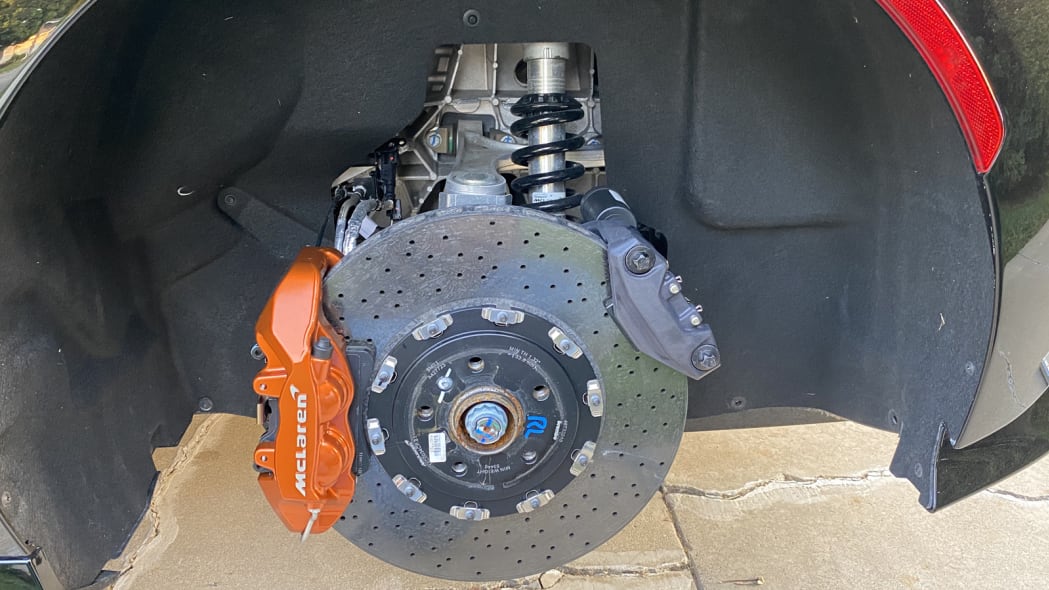

The spec sheet says the rear suspension is a double-wishbone arrangement, too, but we’ll need to get in closer to see more than these brake components.

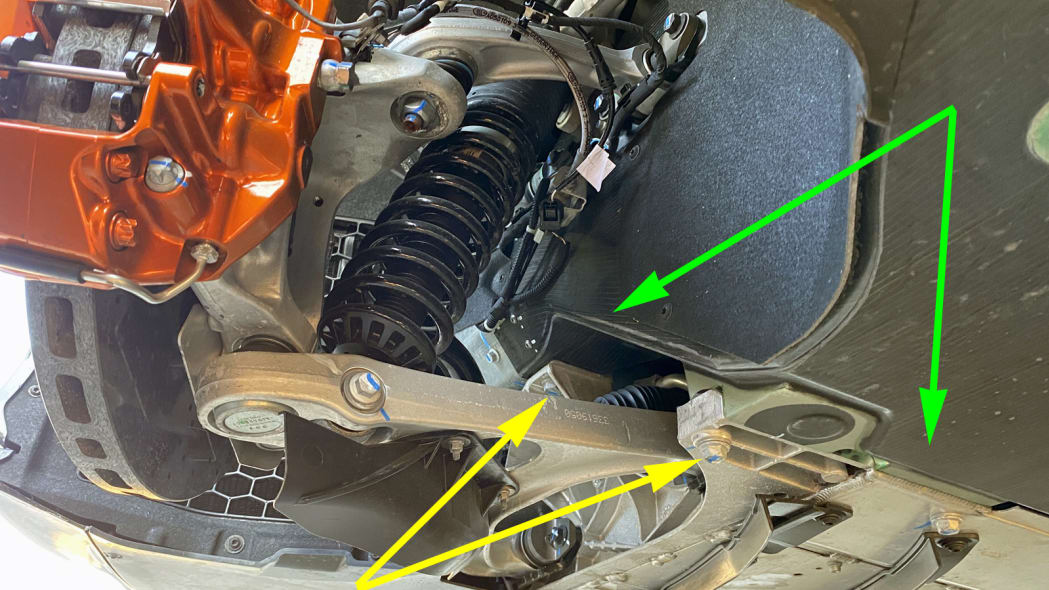

The upper wishbone (yellow) is L-shaped in order to allow room for the rear coil-over, which has numerous grooves (green) that allow alternate positions for the snap-ring that locates the upper spring seat. You would never make such adjustments if you owned this car, but McLaren makes use of different grooves for different models in their lineup that share the same shock body but require different spring lengths and spring rates.

In fact, the GT differs from the 570 in that this rear spring rate was selected to make its rear suspension wheel frequency slightly quicker than its front — much like a normal sedan. The 570, on the other hand, has a slower rear suspension wheel frequency relative to its front, a difference that makes it turn in more directly but also subjects its passengers to a more “porpoisey” ride. This difference represents another one of those invisible tuning parameters, along with bushing deflection characteristics, damping force curves and numerous other details, that has a big effect on a car’s performance and personality.

In case you were wondering, these dampers aren’t very thick. You can do that when the valving is positioned at the top of the assembly in separate lateral chambers. We can’t see them back here with all the fender liner trim in the way, but they look much the same as they did up front.

As we’ve seen elsewhere, the rear upper wishbone is bolted to the chassis using tie bars. The Acura NSX uses the same sort of mounting, but they call them dog bones. I’m not sure which term I like best.

The GT’s lower wishbone attaches to the lower ball joint with what must be a locking nut (yellow), but I admit I’d be much more comfortable with some kind of retaining pin. The toe-control link (green) uses a similar attachment strategy. I also find it odd that the ball joint stud has an internal Torx to stabilize the joint during tightening while the toe link uses hex.

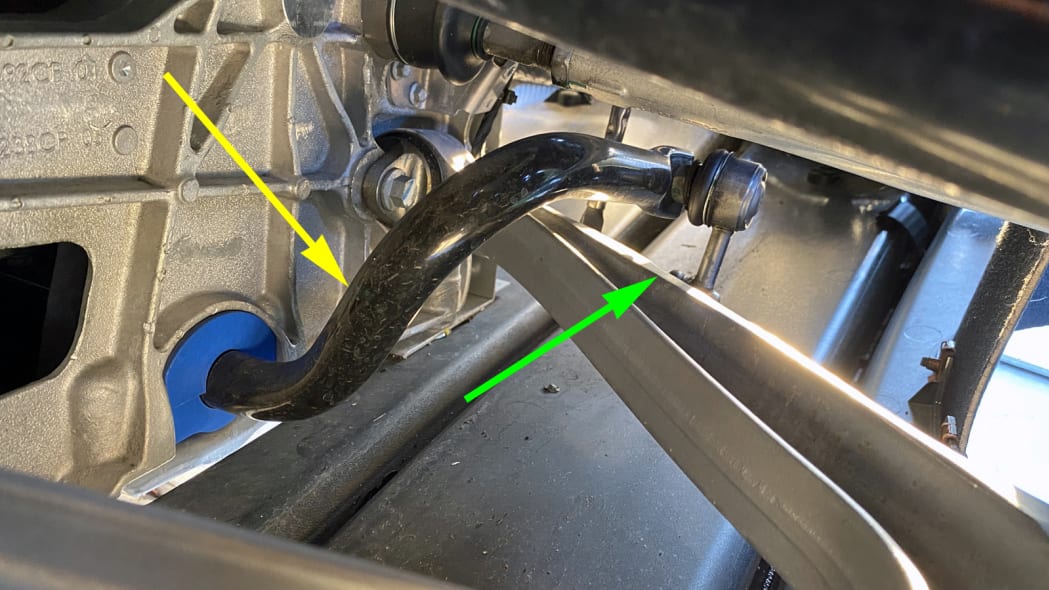

The inner pivot of the toe link (yellow) screws straight into the chassis, but the interesting bit is there’s an unmachined alternate attachment point just ahead. The GT’s chief engineer explained that other models that are designed to exhibit livelier handling utilize the forward location. But the GT, being a GT, is designed to be more predictably stable, particularly when braking or decelerating into a turn. The more rearward toe-link attachment and the GT’s bushing tuning strategy work together to generate a bit more toe-in in such circumstances.

Meanwhile, the lower wishbone (green) is fixed to the chassis with another pair of tie-bars.

Static toe adjustments look a little tricky because the adjuster (yellow) and jam nut are mounted at the far inboard end of the link; the aerodynamic diffuser that makes up the floor of the car would almost certainly have to come off. Nearby, the rear suspension height sensor (green) takes its reading from a point on the lower arm that’s close to the inboard mounting point.

The stabilizer bar (yellow) loops up and over the lower wishbone from its pivot point at the bottom of the chassis. Its short connecting link attaches to the rear leg of the wishbone (green) just outboard of the spot where the suspension height sensor connects.

The McLaren GT’s primary working brake is a four-piston fixed caliper that’s painted an eye-catching color so it draws your attention through the spokes of the wheel. The smaller electrically-actuated single-piston parking brake caliper is painted flat black so it doesn’t.

The GT is the first McLaren to offer 20-inch wheels in front and 21-inch wheels in the back. The usual combination is 19-inch fronts and 20-inch rears. The difference has more to do with how the GT is marketed than anything else.

Still, it’s pretty commendable that the 20×8-inch front wheel and 225/35ZR20 tire assemblies come in at just 46.5 pounds. It’s also unsurprising that the fatter 295/30ZR21 tires and more massive and highly loaded 21×10.5-inch rear wheels add up to 63 pounds.

The McLaren GT is an intricately built machine that oozes thought and craftsmanship underneath. It’s also clear that it’s intended to be a more roadworthy supercar that’s been intentionally optimized to favor the realities of real-world driving over the theoretical possibility of track-day heroics.

Contributing writer Dan Edmunds is a veteran automotive engineer and journalist. He worked as a vehicle development engineer for Toyota and Hyundai with an emphasis on chassis tuning, and was the director of vehicle testing at Edmunds.com (no relation) for 14 years.

You can find all of his Suspension Deep Dives here on Autoblog.

Related Video: